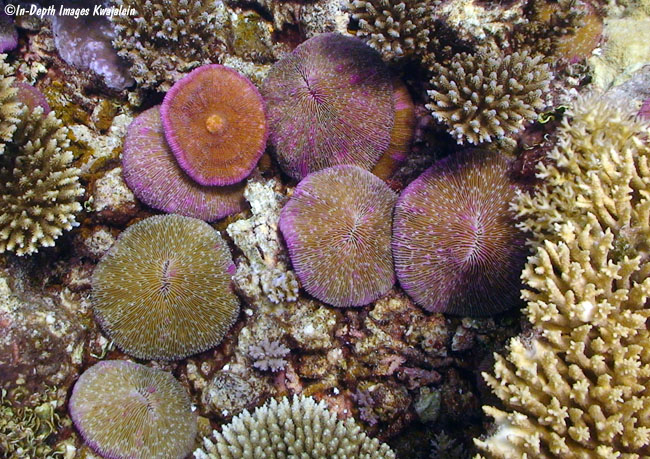

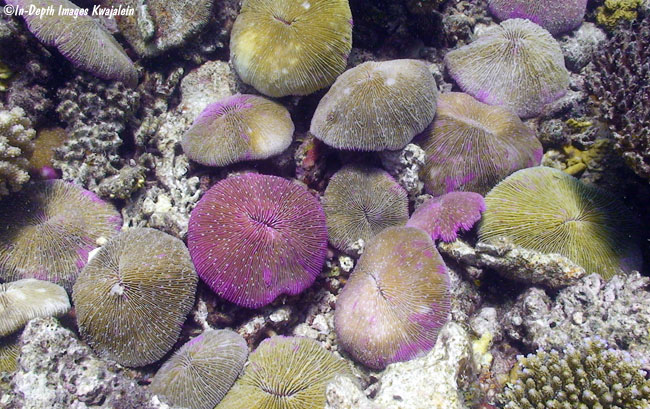

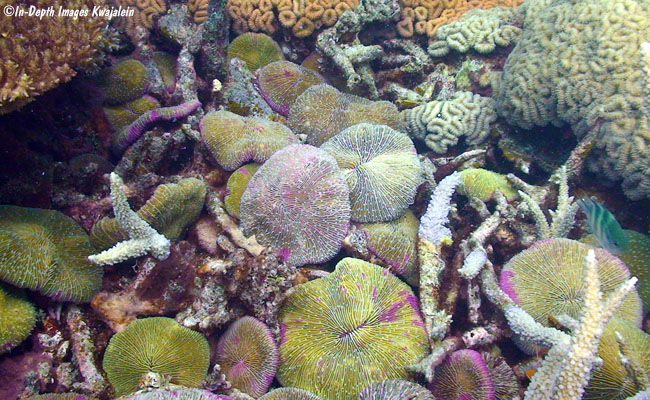

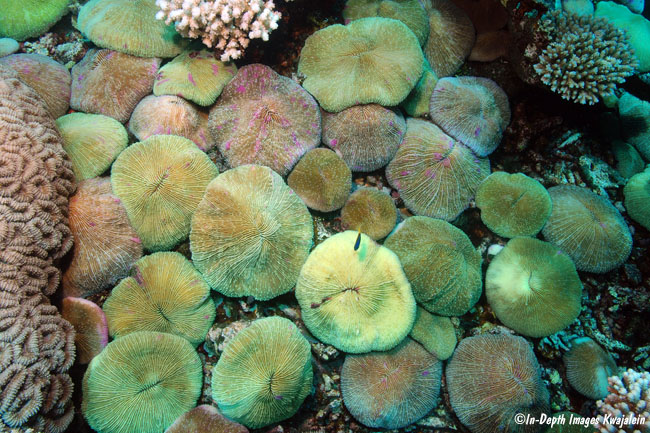

These appear to be Fungia fungites. This is one of the most abundant and variable Fungiids we see at Kwajalein, present in large numbers on shallow lagoon pinnacles and reefs. They are variable in color and shape and have pointed and sharp septal teeth on the sometimes sharp radial ridges (septae) that extend from near the center to the periphery of the polyp. Being loose on the bottom, like most Fungiids, these corals are often flipped upside down by large predatory fish (some large wrasses or triggerfish) who are looking for crabs and other invertebrates hiding beneath. Being upside down with the mouth facing the bottom, the coral would be less likely to feed on plankton or floating food, and the upper primary surface for photosynthesis by the symbiotic zooxanthellae is in the dark, possibly leading to starvation of the coral. I would often spend time on a dive flipping corals upright, so I was well aware of the sharp, pointed septal teeth sometimes puncturing my fingertips.

I think the brown ones with lighter patches are Fungia repanda.

Often multiple species are mixed. This one might also include both Fungia repanda and the elongate Herpolitha liimax.

The bright yellow one appears to be bleaching.

Young individuals.

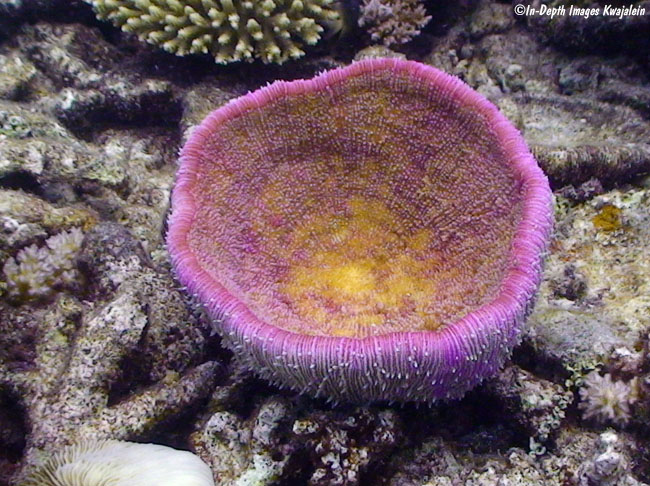

Like most other scleractinean corals, tissue of the Fungiids contains symbiotic zooxanthellae, single celled photosynthetic "plants" (or more properly, Protists) that use carbon dioxide from the coral animal, water and sunlight to produce oxygen and carbon compounds that can be used by the coral for respiration and food. Under some circumstances, the corals lose their symbiotic zooxanthellae. One way is through warmer water that is happening more and more due to climate change. The other is lack of sunlight to power the zooxanthellae photosynthesis. In both cases, the brownish or greenish plants leave the coral tissue, leaving it mostly pure white, although sometimes with some pigment left that is part of the coral animal. Below a normal Fungia polyp is shown next to a pure white one that had fallen into a crack and was in the dark in a small cave. The coral was likely starving but still lived, and I pulled it out to get it back in the sun, where with luck it will again begin to acquire zooxanthellae symbionts and regain color.

The one below is bleached out due to warm water. When the water temperature at Kwajalein reaches 30°C (86°F), many coral species lose their symbiotic zooxanthellae, becoming either pure white or mostly white with some color left over from the coral animal itself. Although diving in the Marshalls many years beginning in the mid 1960s, we did not see widespread coral bleaching happen at Kwajalein until 2009, the first time we saw the temperature reach 30°C. Most years the temperature peaks at 1-1.5°C below that during the fall months, the warmest time of the year. Some of the bleached corals died, but some recovered if they could survive until the water cooled down and their tissues were recolonized by the zooxanthellae. However, the temperature got high again and bleaching recurred in the fall during 2013, 2014, 2016, 2017 and 2018, the last year being especially serious when many coral species died. I have not yet heard what happened in 2019, but it is clear that high temperatures and coral bleaching are happening more and more often. The oceans are most definitely warming up. A few more bleaching photos are on a separate page.

Several Fungiids below are being engulfed by growing Lobophyllia coral, which will eventually cover them up, depriving them of light and killing them.

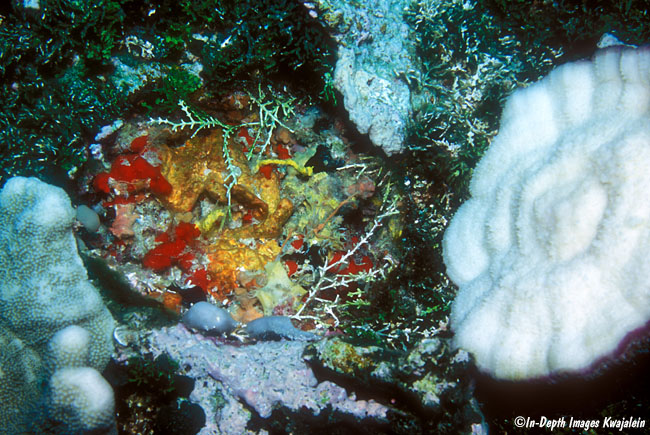

Fungiids are loose on the bottom and can be flipped. The underside of the coral is white (at right) and the bottom it usually covers sport a growth of colorful sponges that do not grow in the light.

If they long survive being flipped over, the edges of the polyp will curl inward, exposing more of the dorsal surface to the sunlight.

By color and location on a southern Kwajalein lagoon rubbly pinnacle, I think these are young "mushroom" stalks of Fungia fungites.

Created 10 April 2020

Updated 9 August 2020