Lambis truncata is distributed across much of the Indo-West Pacific, but is often split into two separate subspecies. Lambis truncata truncata is found in the Indian Ocean, while Lambis truncata sebae (Kiener, 1843) is the form found in the Pacific. It is the largest of the finger shells and is very common in the Marshalls in a variety of habitats. They can be seen in good numbers in lagoon sand and Halimeda algae flats; on rubble and the hard reef flat as shallow a meter of less; on lagoon pinnacles, particularly the large and flat-topped ones; and on both eastern and western seaward slopes, both on the top of the slope and down the sides. Fish & Wildlife, who came to Kwajalein at the request of the US Army to survey the marine environment surrounding islands it leases, chose to recommend this and Harpago chiragra be made protected species. (Although they originally misidentified H. chiragra as L. scorpius.) Curiously, the reason for recommending the protected status was basically that...they were there. That is, specimens were present off the leased islands where they did their sampling, so therefore the shells might get collected. Hmm, you could do a lot with that kind of reasoning. (Tuna are in the waters around Kwajalein and they might get caught, so perhaps they need to be protected as well.) In any case, the recommendations were accepted and these are now protected from sport scuba divers and snorkelers who work as contractors on the Army base. However, the species can hardly be said to be threatened, especially from sport divers, who I'm sure only very rarely ever picked up a specimen as a souvenir. If there is a threat to this species, and I don't really think there is, it is because the local islanders collect them for food. I have seen piles of broken shells collected by Marshallese fishermen in one day that contained more shells than, I'm sure, all the specimens collected by sport divers on Kwaj over a span of years. Yet the local Army regs do not and cannot regulate Marshallese fishermen. I'm not saying it is a good idea to collect them, or that it is a bad idea to discourage collecting them; however, this particular regulation does nothing to add to their protection. Expending effort to protect species that do not really need it dilutes the importance of protecting species that really can use it, such as the giant clam Tridacna gigas. Those are too scarce and their numbers have declined. Unfortunately, the greatest threat to Tridacna is also fishermen harvesting the animals to eat, and there is not much that can be done about that.

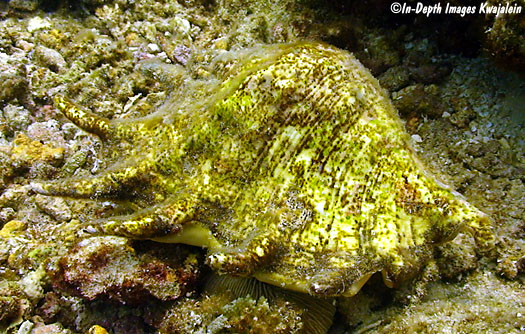

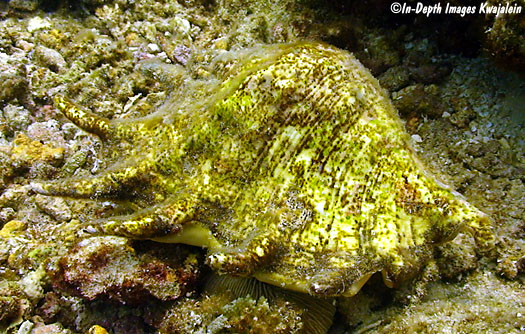

Most specimens are old with worn-off fingers and heavily encrusted with dorsal calcium deposits, up to and including colonies of various corals, such as the faviid coral growing on the shell below.

Here's a real head scratcher. The specimen below was observed in the same area as the one above. The photo above was taken on 24 September 2009, while the one below was shot on 1 June 2010. Could the coral carried by that overburdened mollusk possibly have grown that much in a mere nine months? Or did the one above simply move out of the area and the one below move in? I wish I'd marked it somehow! It seems the large size of Lambis truncata shells makes for a good settling site for coral larvae, particularly in the soft sandy or algae habitats these shells frequent. On another page are further examples of corals on L. truncata shells.

This one's shell is completely encrusted with Millepora fire coral, with the fire coral even encroaching into the living space of the molluscan occupant. I felt sorry for this guy. It must have been painful to extend his eye stalks out through the anterior notch with all that stinging fire coral around. I wished I'd been carrying a chipping hammer to try to chip some of the coral away.

Despite their large size and thick shells, they do fall prey to some creatures. This shell was on a midlagoon pinnacle, far from anyplace where people could have likely broken the shell in order to eat the animal.

This pair in a Halimeda patch are putting down an egg mass, seen as a mass of mucus packed sand just below the shell in the second photo below.

Here's another egg mass just below the shell in the photo.

The stalked eyes peek out of the shell's aperture. Looks a bit cross-eyed.

Here's a group on a Kwajalein lagoon pinnacle. Some of these large flat-topped pinnacles are the best places to see a lot of specimens in a small area.

Created 1 October 2009

Updated 11 April 2023